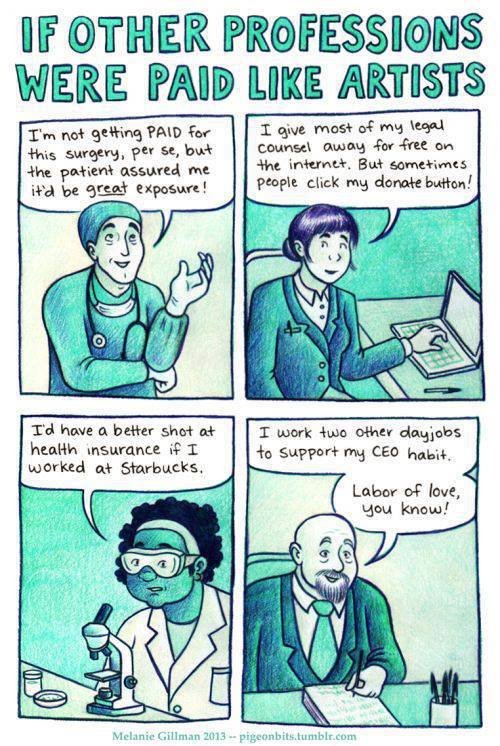

If other professions were paid like artists…

Why do so many artists get asked to work for free, so often? And what's the best way for an artist to deal with these requests, and ensure they're financially secure and their work is valued? Michelle Aldredge explores the problem and encourages 'mindful decision-making' as a way forward.

Recently, a visual artist friend posted the following on her Facebook page: ‘Just for the fun of it, I counted up how many times in 2014 I’ve been asked to do work for free, but for the distinct financial benefit of those asking. A donation, if you will. Eight times so far, six weeks into the year. I knew I was asked a lot, but I didn’t realize the average was more than once a week. If only paying jobs came with the same frequency.’

There are few professions where individuals are expected to give away their time, talents, and ideas. And yet artists are expected to do so on a regular basis. Why? Maybe it’s because the larger culture has discovered our secret: that most of us will make art even if it doesn’t make money. Most artists create for the joy of the process, because they have something to say, and because they must – it’s as essential as breathing and eating.

While it’s true that even lawyers and doctors do pro-bono work for causes they believe in, there is a primary difference: they aren’t expected to give their services away on a daily basis. It’s their ability to earn a stable living that allows them the luxury of being generous and donating their time and services. Financial stability gives them choice. In other words, abundance (however you define this word) allows generosity. It allows us to give back without harming ourselves.

‘Abundance’ will be defined differently for each person, but most of us can make do with less than we think we can. And yet simplicity is not the same thing as poverty or insecurity. Artists need to have security in order to thrive. We need our mental and physical energy free for our creative work and the business of promoting it. Worry drains our energy.

Artists excel at bartering, especially with each other. (This is another reason we are so often asked to give away our work – bartering is a familiar currency in our world.) Personally, I’ve benefited tremendously from the gift economy, and it can be a huge help when exchanges are mutually beneficial.

But problems arise when the balance of power is unequal – when we are asked to give more than we receive in return. This can create resentment, especially when time, money, and energy are scarce. The result is that we feel depleted, stressed and ashamed, because we have not taken care of our own well-being first.

Mindfulness and money

What is the solution? Mindful decision-making. My friend, who counted up the number of times she had been asked to give away her work, took a crucial step – she quantified these requests. Now that she is aware of how many of these are coming in, you can bet she is going to think twice each time she is asked. She now realizes that saying “yes” to something means saying “no” to something else.

Taking care of our own financial needs is not selfish, it’s essential. And like the doctors and lawyers who donate time to causes they care about, abundance, as well as balance, will allow us to be generous when we are approached for a donation.

We all carry around a lifetime of subtle (and not-so-subtle) cultural and family messages about money. These money myths become so ingrained that we forget to question them. We assume they’re true, when in most cases they’re not. Too often we simply coast on auto-pilot, not examining our decisions and often saying “yes” when it should be “no” and vice versa.

Do any of these distortions about money sound familiar?- People can’t afford the art, services, music, etc. that I create.

- If I follow my passion and do what I love, I won’t make money.

- I’m ‘selling out’ if I set my prices appropriately and charge what I need to charge to make a living.

- Price is what matters most and cheap sells.

- Money corrupts. I’m a better artist without it.

- I am doomed to be a starving, struggling artist forever.

- Being a successful artist in a capitalist market is impossible.

- It’s not fair that artists have it so hard in this society.

- It’s not fair that other artists are more successful than I am.

- My ideal customer is someone like myself or my friends, and since we’re struggling artists, I should keep my work affordable.

- It’s not cool/ladylike/hip/proper to talk about money.

- My gut tells me to say “no” to giving away my time, but I have to say “yes” to stay on this person or organization’s good side.

- If I keep giving away my art and services, someone will eventually notice and appreciate my work.

- (And the most insidious of all) I’m not worth it. I don’t deserve to make a good living doing work I love. (This is shame talking.)

Seek out abundance

It’s time for artists to discuss the topic of money openly and without shame. We can’t expect abundance to simply fall into our laps – we need to seek it out. We need to know what our goals are financially. We need to quantify them, write them down, and mindfully draft an action plan that will help us achieve these specific goals.

Yes, it’s true that our culture isn’t easy on artists. And yes, being an artist is hard work, even when the money does come in. But too many artists have accepted their role as victims. Perhaps it’s time to move past the things we can’t control, and instead, focus on what we can control.

We can’t control the competition pool for grants and residencies and shows, for example, but we can control how we present and price our work and how often we apply. Perhaps a day job is necessary right now, but is it also necessary to stick with grueling work that is an ill fit with our creative lives?

As artists, it’s time to shift our mindset from one of scarcity to one of abundance. Pricing our work appropriately, saying “no” when necessary, and setting concrete financial goals for our creative practice are signs of self-respect. The larger culture exploits artists, in part, because we allow it. We may not be able to change the world, but we can certainly change our response to it.

This is an edited version of an article originally published on www.gwarlingo.com